Wednesday, December 22, 2010

The Great Migration

Monday, December 20, 2010

Whoever said money can't buy happiness didn't know where to go shopping

Ugh. And the worst is I'm almost disgusted with myself in advance because I know I'll be making use of it all the time...

Thursday, December 9, 2010

Snijeg!

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

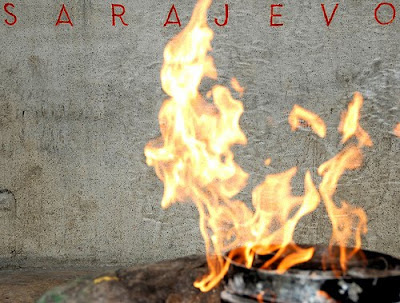

Eternal Flame

šala Tita, one of the main arteries running through the city centre, outside the fading bulk of an Austrian imperial mansion - previously the city's grandest hotel, once a makeshift Nazi prison during the wartime occupation of the Balkans, now a government ministry of some kind - sits Sarajevo's eternal flame.

It's not hugely ostentatious. An alcove built into the building's porch is carved with names in that squared, art deco font universally used on Soviet memorials; the alcove curves around a small green metal laurel wreath on the pavement, which contains a flame like a small campfire.

The flame commemorates those who died during World War II; specifically those who fought as partisans against the Nazis for the liberation of Yugoslavia. Not that anyone really talk about it in that context any more, of course; the partisans simply fought against tyranny in the name of freedom. Best not to mention the politics that surrounds the memory of that hard-won state. Somehow, in general, the Yugoslavian resistance manages to be remembered as the fight for the freedom of its' constituent peoples, even though those peoples many years later started killing each other so brutally.(Wish I could take credit for them but the photos are courtesy of Blaseur and Maciej Dakowicz)

Thursday, December 2, 2010

Free Ali: Hilary Clinton's visit to Bahrain

Hilary Clinton arrives in Bahrain tomorrow on an official state visit. Jenan Al Oraibi, wife of Ali - who I have written about previously - has this evening issued an open letter asking Mrs Clinton to raise the issue of Ali and the other Bahraini political prisoners' torture and ongoing arbitrary detention with the highest political authorities in the country.

Spread the word.

The distinguished Secretary of State, Mrs. Hilary Clinton,

Pleasant greetings,

I am the wife of arrested Bahraini blogger Ali Abdulemam. Ali is the father of my four year old son Mortada and my twin daughters Sarah and Fatimah who are younger than a year old.

I have received news of your impending arrival to my country Bahrain. I would like to send to you my urgent appeal for help in the releasing of my husband who has been imprisoned in Bahrain since September 4th of this year.

My husband was arrested after being summoned before the National Security Apparatus with accusations – which were never proven – of “spreading false information.” The National Security Apparatus publishedan explanation immediately following his arrest . After a global campaignby bloggers and defenders of the freedom of opinion and expression and human rights , instead of reviewing the detention order of my husband, his arrest was publicized in the media and he was depicted as a terrorist in the media and government communiqués.

Madam Secretary,

It has become clear to me that my husband has been subjected to the crudest forms of torture and physical and psychological abuse throughout his time in prison. He was forbidden from meeting with an attorney throughout the harsh investigation and his time with the public prosecution. In fact, my husband met with his lawyer for the first time in the courtroom. The court also denied the lawyers’ requests to present the barbaric torture my husband was subjected to. The court continues to proceed with the prosecution of my husband based on coerced confessions that have no connection with my husband’s personality, which is known by all the people of Bahrain, especially his family and blogger friends all over the world. Furthermore, the media has refused to publish the torture and abuse my husband was subjected to or the proceedings of the trial which we know are full of difficulty and hardship.

Madam Secretary,

My husband was fired from his job at Gulf Air which he was devoted to for thirteen years without a single accusation or examination by the investigative council. Thus, with my husband’s arrest alone we are immediately faced real suffering that increases with the continuation of my husband’s absence which agonizes me and his three children.

I wish to inform you Madam that I consider all that we have faced as a family and all that my husband has faced up to today as a result of my husband’s sincere expression of his views and aspirations in reform and goodness for Bahrain and the region. My husband protests peacefully through blogging on what he considers to be harmful to the interests of the people. Ali supports and calls for reform in Bahrain and Iran by devotion to individual freedom and the freedom to express one’s opinion. That much is obvious from his blog posts.

Madam Secretary,

I am certain that you will meet with the highest officials in Bahrain on your anticipated trip. I am also certain that those officials will immediately comply with any appeal from you to enforce justice and release my husband. Therefore, Madam Secretary, I implore your sympathy, and all that is provided for in the values of American freedoms, as I appeal to you to include my husband’s case on your anticipated trip’s agenda. Your support will surely strengthen the value of democracy and freedom which support the development of justice, peace, and tranquility.

I would like to thank you for taking on this moral responsibility. I sincerely hope you will support my request.

Jenan Al Oraibi

The wife of arrested Bahraini blogger (Ali Abdulemam)

Saturday, November 27, 2010

Saturday afternoon, Sarajevo

Monday, November 22, 2010

Korčula, Croatia

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Aung San Suu Kyi and Ali

“I was subjected to torture, beatings, insults and verbal abuse. They threatened to dismiss my wife and other family members from their jobs. I was interrogated in the prosecution without a lawyer, and the officer there who appeared to be from the National Security dismissed my denials to the allegations put against me. He never allowed me to respond to the questions he was asking, but rather answering them himself whilst I was stood behind the door as I was not permitted to sit during the investigation".A blog run by Ali's supporters has in addition reported that he was hung from the ceiling, blindfolded, beaten, cursed and insulted.

Friday, November 12, 2010

"Welcome Back to Sarajevo"

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

The Heavy One

Unfortunately that impression didn't last long. Within days I began to see that the city is so young because it's youth are so disaffected and have nowhere to go but to the cafes and street corners. There is significant begging - you can write them all off as the gypsies if you're so inclined, but they are still poor people sitting on the street. The elderly especially look worn out by a lifetime's troubles: they trudge with shopping bags, wearing headscarves and old overcoats, their faces lined so that I have no way of telling if this is really middle or old age.

Some buildings are still bombed although most of the city centre has been rebuilt. Many more buildings are still-bullet scarred: no one has got around to replastering yet. On the day I moved into my apartment I noticed that the wall of the house next to mine, which faces my living room window and is not more than five feet away, is pock marked and scarred. My house faces the hills; it's to be expected. I presume that they've simply repaired my building.

The strange thing is that this already seem pretty commonplace. I don't wander around gaping at bomb-marks. But it's an ever present reminder that bad things happened here very recently, and that I don't have to live with the memories of those bad things like almost everyone else here has to.

Monday, November 8, 2010

Smoke gets in your eyes

Friday, November 5, 2010

Contradictions

Sarajevo is a funny little city. A few contradictions in terms which I’ve noticed this week:

The place is buzzing. The main street is continually thronged with neighbours wandering up and down, spotting the talent and gossiping. Its bars and cafés are packed all day, every day. On weekday afternoons you can’t get a seat beside a window anywhere on the main streets. This seems to me entirely at odds with Bosnia’s poverty stricken economic situation: why does the nation look so leisured? Why aren’t they all out there somewhere ‘struggling’? The reason: the 46% unemployment rate. Almost a full half of the working population literally seem to have nowhere else to go and nothing better to do all day, every day. At least they seem to spend their time sociably.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) has a 46% unemployment rate and is still struggling to overcome the economic and industrial destruction of the war. What seems a curiosity to me however is the certainty of this magic number: how can they calculate an exact unemployment rate, when there has been no census carried out since before the war. The authorities have very little idea of exactly how many people are in the country, where in the country they are (a highly significant issue in this federally divided state), what ethnicity they belong to, or which of the many governments they vote for.

As for the government, don't get me started. I refuse to even begin describing it here, but BiH is divded into state, federal republic, cantonal and local governments, all of which I suppose are a source of that all-important employment. You thought Belgium had it bad? Try a country smaller than Ireland which has 162 ministries. The political arrangements are so complicated that frequently there is no clearly defined hierarchy between ministries, governments, civil service departments or even the courts. And similar to the census, it seems to be more convenient for the sake of many interests not to have to clarify things.

The popular perception of BiH as a conservative Islamic society. Reports of the war, the atrocities carried out here, the post-conflict rebuilding efforts and the war crimes trials all described the effect of the conflict upon a particularly enclosed, modest, traditionalist community: of ostracisim and stigma and shame. Yet this simply doesn't seem bourne out once you're here. Take the female victims of the conflict for example, hundreds of whom have been exceptionally brave in testifying to the courts about their experiences without suffering rejection or shame. I can’t speak for rural areas, but in Sarajevo at least there is no such thing as conservatism: couples kiss on streets, beer and the rakia (plum brandy, local moonshine) are flowing, the nightlife goes on for six rather than two nights a week, and hem lines are short. Really short. Shorter than I would ever wear… certainly shorter than I’d wear in conjunction with the fake tan and the FMBs and the blond highlights. The style on a night out here is something quite shocking. Conservative, moi?

And last but not least: the contradiction of the beautiful women. They're stunning. On my first afternoon here, wandering around the streets while I tried to find a lonely traveller’s supper, the sheer beauty of the girls was startling. The heels, the hair, the dresses. The eyes. Those cheekbones could kill a man. And the contradiction? The women are so beautiful, and the men, well, are… not. I won’t offend any Balkan male sensibilities by going any further. But one-sidedness this marked is a contradiction. And going by the reactions of the (predominantly male) backpackers in the hostel, Sarajevo is a good place to be a guy.

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

Vaulting myself back up onto the blogging horse

From my perch under the eaves, past the mosques and the minarets, past the Sebil fountain which promises a lifetime in Sarajevo for those who drink its waters, I look out on the hills ringing the city, which at this hour after dark twinkle in the distance. Sarajevo is a neat little city tucked into a tight valley, its gabled houses spreading up the hillsides like mould speckled on a bathtub. The Centar is long, narrow and pointed, probably no more than 500 or 600 metres wide, so that at most moments as you move through the city you can see a steep hillside beginning close by on both left and right sides. On cold mornings the city is a bowlful of mist and fog lit through by sunshine. On clear nights, lights twinkle on either side like pierced cloths have been strung across the sky. And when it rains – as it did for two days without pause last week – it felt like we lay in the bottom of a cistern.

Thanks to my friend Sven from whom I shamelessly robbed this photo without his knowledge.

Sunset on Sunday 31 October 2010

From my office on the 14th floor of one of the city’s only skyscrapers, I have yet to get tired of the view, one of the strangest mixes of a vista I think I’ve ever seen. Tapering up to the hills which begin only 200 metres away and which are dusted with the year’s first fall of snow, I can see the minarets of Turkish mosques, Austrian-style red gabled houses, socialist tower blocks, gracefully engineered mountain-side roads, a Croatian supermarket chain, a Chinese restaurant, an empty new shopping mall and the improbably smooth and gleaming Parliament building, rebuilt only in the last few years after being burnt during the war. My own skyscraper was shelled early on during the siege. I try to imagine it at as I listen to the hum of central heating and printers and the jingle of new emails, looking down at some of the bullet-scarred buildings below. The tower must have projected its 21 storeys of desolation over the low-lying city like some kind of spectre of the nightmare.

Sarajevo reminds me in lots of ways of Cork. It’s probably about the same size: 300,000 people, with a tiny, twisted centre and a sprawl of suburbs. It seems full only of young people, packed with old bars to which you need directions, little families running closet-sized cafes. They even have a jazz festival starting this week and of course, the locals speak a tongue-twisting lingo which defies all attempts of translation!

I may be starting Bosnian classes next week – another intern from the office is organising a teacher so I have decided I may as well embrace the opportunity, if only to manage ordering food, taking taxis and getting a coffee that actually corresponds to what I wanted in the first place. Bosnian is called Serbian in Serbia, Croatian in Croatia, and Slovenian in Slovenia, but it’s also almost the same as Czech, Slovak, Bulgarian and Polish. The touristy cafes in Bascharciza have waiters who can snarl “Pancake? Mixed grill? Soup?” at you when they see you looking confused, and the taxi drivers who claim not to speak English mysteriously know how to explain their charges, but in general it’s more difficult than I had anticipated to muddle by without the language.

Take Mr Brano, the caretaker of my apartment. I found the place through an agent, who handles all contact regarding the apartment in lieu of the landlord, who lives abroad. The agent, poor thing, is also my personal translator as Mr Brano does not speak a word of English. And I do mean literally, not a word. ‘Please’, ‘hello’ and ‘thank you’ mean nothing to him. I suppose he must be in his 60s, wearing frayed trousers with a few faint streaks of paint and sturdy winter boots. On Friday he was waiting at the apartment to meet me when I arrived, three friends (i.e. helpful bag-carriers) in tow, huffing and puffing and rushing in with suitcases. We had to wait half an hour for the agent to arrive and sign off on everything.

While waiting, Mr Brano carefully and thoroughly walked me around the apartment, showing me with the delight of a skilled craftsman how each individual switch, plug and fitting in the place worked. All of it was accompanied by a stream of detailed description in darkest, densest Bosnian – it was entirely irrelevant to him that I – and my three friends - didn’t understand a single word. He revealed how each individual light fitting, table lamp and spot light turned on and off. He demonstrated how to light the gas stove. He opened the fridge and gestured to show me it was cold. He opened and closed the windows, he slid the venetian blinds back and forth, he turned the shower off and on. He gave a thorough and complex demonstration of the sliding doors of the fitted wardrobe in the bedroom. He showed me the blankets in the closet and the drawers built in for storage under the sofas. He indicated the television and showed us the channels, but he reserved particular attention for the thermostat for the central heating. 20 degrees would be about normal, but because the place hadn’t been heated in months it was turned up to 30 for the afternoon. This required a tremendous explanation on his part; never mind that it was entirely unintelligible – he gave me the most thorough convincing of the merits of turning the temperature down to 10 or 15 while I was out during the day, before putting it back up higher at night. 30 was too high! 30 was only for today!

“Super, super,” I nodded, knowing no other word to express my anticipated pleasure with all of this. He seemed delighted – I think he sensed my profound appreciation of the marvellous system of switches and lighting in the apartment! I know that I certainly had a profound appreciation of the agent when she finally arrived and could reassure Mr Brano that I had understood everything. He went home for the weekend, happy with what seemed to be the gratification of a well-satisfied craftsman.

Mr Brano is probably one of the reasons I want to learn a little Bosnian. I want to be able to say thank you, or make small talk. But I also want to be able to say something to sweeten the old ladies who frown at you sceptically as you walk down an uneven street of patched concrete houses. I want to be able to get bartenders to take me seriously and bother to serve me rather than pass me over for the beautiful – no, strike that – stunning, all the women here are absolutely stunning – girl next to me at the bar. On my third day it took at least four minutes of wild gesturing and pointing and pulling faces to get the man at the deli to cut me some cheese. I want to be able to order coffee and get it right. I’d like not to get jostled on the tram.

I think it’s just that the Bosnians are tough, and I don’t think anyone would hold that against them, all considered.

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

Miss Sarajevo

Monday, October 25, 2010

I'm back!

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

Ireland

I flew out from Kampala on Friday night, and arrived back in my small little Irish home town on Saturday lunchtime. By Sunday afternoon I was already on my way to Dublin and on Monday morning I was back at my old desk in the office, fumbling my way uselessly through the same work I was fluent with a few months ago.

There's so much I haven't written about - so many things happening, so many places seen, new people befriended, new journeys made, new events (some magical, some tragic and horrifying). This blog was as much for myself, to remember things, as it was for anyone to read about them. The month of lost blogging thus really does seem a loss - too many things I'll have forgotten, some day. It's not that I gave up blogging the past month, its simply that circumstances conspired against it. Armenia swallowed a large chunk of my Ugandan time - I spent ten days away. I spent a week recovering (literally - a large proportion of the week after I came back was spent in bed recovering from some kind of bug I picked up along the way). I spent another week almost totally without internet in the office, frantically trying to wrap up the work I needed to finish before my successor, Daniel, would arrive for a handover. My last week in the office was only three days long, all of which was swallowed by workshops, speeches and the launch (a big deal) of the Human Right's Centre's first report. And then I spent about a week traveling with two friends through southwest Uganda and Rwanda before coming back to Kampala to fly home.

It would take me days to write about our Great East African Road Trip. Suffice to say it involved:

- Crossing the Equator for the first time. Disappointingly the world is not as upside and back to front down there as one would hope.

- A series of long-winded bus journeys, the last of which was ten hours long, which all seemed to involve broken bags, babies on laps, questionable roadside food, near-death experiences on Rwandan mountaintops, Nigerian soap operas, Christian music, the total absence of personal space, amorous Ugandan and Rwandan men, out of date newspapers, postal deliveries and sore bladders.

- An inexhaustible succession of Scandinavians of various shapes and sizes.

- Africa's deepest lake, and wooden dugout canoes upon it, and fish inside it, diving into it, and lying in hammocks beside it.

- Day-long card games, which no one ever won.

- An earthquake. Yes, really, an earthquake. It was a good 5-10 seconds long and as thrilling as it was bloody frightening.

- Crayfish. Oh god, so much crayfish. So delectably good. Sigh.

- Omelets. Some good, some bad, always reliable.

- Unfathomable and indecipherable exchange rates. I currently have six different currencies in my purse.

- Walking to the Congo, standing and looking at the Congo, and ultimately failing to get into the Congo. Must go back to climb the volcano another time.

- Incorruptible Rwandan border guards. We would know - we tried our very best to corrupt one, and emerged morally bankrupt. Absolute shame on us.

- Children - hugging us, squealing at us, being dumped on our laps. Life affirming.

- Genocide memorials. Really nothing witty I can say about this.

- Terrorism.

We were safely in Rwanda when we heard the news, and thankfully no friends or colleagues were affected. This is less surprising than you might think - one of the bombs, at the Ethiopian Village Restaurant, went off in my neighbourhood, Kabalagala (which I've written about before), about halfway between home and the office. I've driven past twice a day for the past three months; I've eaten there before. If I had been in Kampala I probably would have been in a neighbouring bar or restaurant that night - in fact a good friend of mine was in a place just up the street and heard the explosion. But noises and whooshes and bangs happen all the time in Kabalagala, especially on the night of the World Cup Final, and no one took any notice. Fifteen people died in that whoosh.

I've been trying to explain to people that while you in Ireland or Europe or North America might think that these things happen "out there" all the time, in those far flung places whose names are linked to suicide bombings every week, these things did not happen in Kampala. Security concerns in Kampala involved taking precautions against petty theft, or avoiding political rallies and protest demonstrations where rowdiness and beatings are a growing trend in the run-up to the elections. No one worried about bombs and fundamentalism and extremists. Kampala was - and is - a city of bars, and shacks selling beers, and restaurants with live music; a town obsessed with football, where even the rundown local joints screened satellite channels from South Africa; a place where a typical Friday night out involved changing your bar every hour until 5am, before sipping beers through the sunrise and dryly taking a boda boda home after grabbing the first rolex from a street vendor at 7.00.

Bombs in bars didn't happen in Kampala. I only returned on Thursday night before flying out on Friday, but you could see the place was jumpy. People are calling in suspicious packages to the police, and shopping bags are checked by security guards going into shopping centres. The embassies send regular text messages with up dates to ex-pats. Yet even still, town was buzzing. "The jam" was as bad as ever, the street food sellers were doing their usual trade, and although the Western muzungu bars were probably deserted, friends have told me wild stories about spontaneous house parties that were thrown up around town all weekend.

I hated hearing about them: I wasn't there. I was watching soft, gray Irish rain beat off the window panes in Kerry, paying €3 for a cup of the coffee I'd so craved, hearing - before I saw - the girls in fake tans and tracksuits. Well, that's a harsh invocation - Ireland's really not that bad. Today, my second day at the office, was better than yesterday, my first. True, the sun was shining today, and I'd forgotten how beautiful Dublin is when you take the train out along the bay; had forgotten the smell of the sea; was startled once again by how O'Connell Bridge at 8.30 on a fine summer morning has the strange quality of a film set - tidy, vivid, wide, calm. And yet, still, what continues to upset me is not that I'm so unhappy here but the fact that I'm already settling back in; the fact that I can get on very well outside Uganda and that I'm already forgetting it and re-adjusting, faster than I want to.

You don't realise how immersed you are in Africa until you leave it; going to Armenia and then returning was in this sense a very strange and emotive experience for me. Reverse culture shock for me isn't, after all, the unfamiliarity of what should be the home environment. It isn't no longer feeling at home in your own place, amongst your own people. It isn't seeing the same old same old with new eyes, marvelling at what you never bothered to notice before.

Reverse culture shock for me, upsetting and disorientating, is in fact the inevitable, crushing sameness of everything when you come back. Nothing has changed. This is obvious, as much to me as it is to you, reading this, and its the almost-sense of shame and stupidity that comes from knowing this and recognising this, the whole, well, what else did you expect?

I've tried to reason it all out the past four days. The obvious answers are: you have changed, and home has not. You have changed, but the people at home have not, and most of them cannot relate, and most of them really aren't all that interested anyway. Other friends who have traveled to the developing world have talked to me about how friends, family and acquaintances project a defensiveness when you return - even if you were never to talk about your experiences, they expect you to, and expect you to express dissatisfaction - which they take to be a criticism of themselves - and expect you, somehow, to project a sense of superiority because of what you've done and where you've been. And even if this couldn't be further from the truth, it won't make any difference to those who'll keep you at arm's length because they expect to find you changed. And you don't want that to be the case; you just want your friends, who you very likely missed while you were away.

Reverse culture shock is all of these things, and yet for me that's not exactly it either. In addition to all of that, there is the sameness of things flattening everything else out. The sameness took the good out of all the modern conveniences that I looked forward to my last week in Africa, trying to console myself at the thought of going home: the long hot showers, the drinking water direct from the tap, the bewildering choice of food, the fast internet, the being able to go out alone after dark. Home is so utterly and crushingly the same, from the instant that you get back here, that all these things are just the same too, unnoticed and unappreciated. I thought I would have forgotten how to drive, or would marvel at the hundreds of choices in Tesco, but I did not. I thought I'd never been able to choose what to eat for lunch, but I just got on with it, and that was what was most upsetting.

No matter how long I'd been in Uganda, no matter how comfortable I felt there, every so often there would come a moment - of beauty, of kindness, of friendship or simply of something random that could only happen in Africa - and you'd jump in your own skin, look around and think - This is amazing. How did this happen? How did I get here? I can't believe this is my life now!

Yesterday, running late for work, lacking change for the bus, getting wet in the rain - that crap Irish half-rain, muggy and humid with mildness - it was my very first day and yet simultaneously so eternally as if I'd never been away. And I looked around and though.... how did this happen? how did I get here? is this really my life?

Because when I thought about where I had been only five days ago - bumping on buses over the Rwandan hills and the Ugandan plains, laughing about nicknames with Jenny and John, being welcomed by the Rwandan border guards who remembered us from passing through on our way the week before, flying on a boda boda through the balmy Ugandan evening, being called Auntie by Mama Sharon and Paul the boda driver, looking at Kampala's twinkling nighttime hills with Paulo, having pizza while surrounded by friends on my sofa, getting ridiculous text messages from Hubert, seeing the tears in Sharon's eyes, guiltily thinking of the people I didn't even get to see before I left, eating chapatti, gossiping over lunch with everyone from the office, listening to the birdsong and the rooster crowing and the call to prayer in the morning, counting banana trees on my way to the airport - I had no idea how I had come from there to here in what seemed like the passing of a few moments. The idea that all of that was over was so deeply upsetting. I wasn't ready for it to end. I still amn't.

I don't know if I'll keep blogging. If I have the time there are stories and thoughts about my last weeks there which I'd like to write about. I wouldn't be surprised if this is the kind of thing which simply loses momentum in the atmosphere of home, although I try to tell myself I'll be different this time. Perhaps this is my last entry, until my next travels; the thought makes me think of the very last anecdote I have from Uganda, and of how perfect - in summing up, and in all the hopes I have for the future - it was.

On my last morning I went to a supermarket to buy an extra bag for my luggage. I took a cheap holdall to the till, where the man whose job is to pack your shopping bags picked it up and turned it over, folded and unfolded it, opened and closed it, and handed it to me as if he'd made it ready for me.

"Thank you please. This is a very good bag," he said, and it wasn't small talk. He really meant it. "You must be planning a journey if you are buying a bag. Eghh. I wish you safe travels ,and good health wherever you will go with it."