On Mar

šala Tita, one of the main arteries running through the city centre, outside the fading bulk of an Austrian imperial mansion - previously the city's grandest hotel, once a makeshift Nazi prison during the wartime occupation of the Balkans, now a government ministry of some kind - sits Sarajevo's eternal flame.

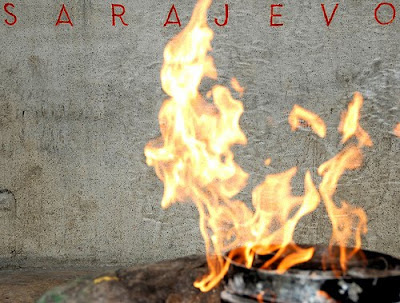

It's not hugely ostentatious. An alcove built into the building's porch is carved with names in that squared, art deco font universally used on Soviet memorials; the alcove curves around a small green metal laurel wreath on the pavement, which contains a flame like a small campfire.

The flame commemorates those who died during World War II; specifically those who fought as partisans against the Nazis for the liberation of Yugoslavia. Not that anyone really talk about it in that context any more, of course; the partisans simply fought against tyranny in the name of freedom. Best not to mention the politics that surrounds the memory of that hard-won state. Somehow, in general, the Yugoslavian resistance manages to be remembered as the fight for the freedom of its' constituent peoples, even though those peoples many years later started killing each other so brutally.On 28 November - Bosnia and Herzegovina's National Day, the day in 1943 that Yugoslavia declared its modern boundaries, although the occupation lasted into 1945 - the country's three presidents laid wreaths in memory of those partisans before the flame. Two days later, on the 30th, the flame went out. It's still out. Eternal no more.

Nothing I've seen here so far has for me summed up so perfectly the state of this small little country. The eternal flame sits to the side of a wide pedestrian area, where the unemployed and disenfranchised youth of the city walk aimlessly up and down the long, straight Ferhadija all evening and afternoon, gossiping and checking out the other unemployed and disenfranchised youth. The odd tourist poses for a picture in front of the flame, girls approach it to bend elegantly over their high-heeled boots and light their cigarettes, and the beggars stand around it warming their hands. Otherwise, no one takes any notice of it at all. So short, unceremonial and unattended was the wreath-laying on the 28th that a friend who lives directly across the street didn't notice anything going on outside.

And now the flame's gone out. A few days afterwards someone took away all the wreaths, and since then it's just been sitting there, unlit. The thing that strikes me is that no one seems to care. The internationals and the ex-pats are appalled: chatting about it at the Organization meets with small gasps of shock and shaken heads at this terrible faux pas, this symbolic gesture of neglect and disfunction. But there's been nothing about it in the press (or at least in the English-language consolidation of the press that we read, which usually reports almost exclusively on issues of governance, reconciliation and the international community). There's been no official explanation of whether it's due to a fault, or a dispute with the gas company, or for maintenance work, or whether it'll be relit at all. It's just gone out, one more thing that doesn't work properly - neglected, faulty, disparaged, disassociated - in a country which I've heard described a lot more than once since I got here as a failed state.

That image of beggars warming their hands around the flame, of teenagers indifferently using a memorial to light their cigarettes, stays with me. It seems a natural progression to the abandoned metal bracket on the pavement, no longer symbolic of anything.

So much for the memory of the fallen partisans; so much for all that shared history before 1991; so much for violence which had at least a common purpose; so much for commemorating anything that doesn't reflect your own ethnic group's victimhood.

Just another day in the Former Yugoslavia.

(Wish I could take credit for them but the photos are courtesy of Blaseur and Maciej Dakowicz)

No comments:

Post a Comment